Ecology, Evolution, and Bioinformatics

I have been studying giant viruses since I began my Ph.D. program at Kyoto University in 2019. At that time, there was no universal approach to identify this group of eukaryotic viruses with giant genomes. Shortly afterward, two major papers were published in 2020, using metagenomics to study giant viruses. At the same time, the ICTV officially classified this group of viruses as Nucleocytoviricota. These developments were inspiring and significantly influenced the direction of my research. During my Ph.D., I have been using metagenomics to investigate various aspects of marine giant viruses.

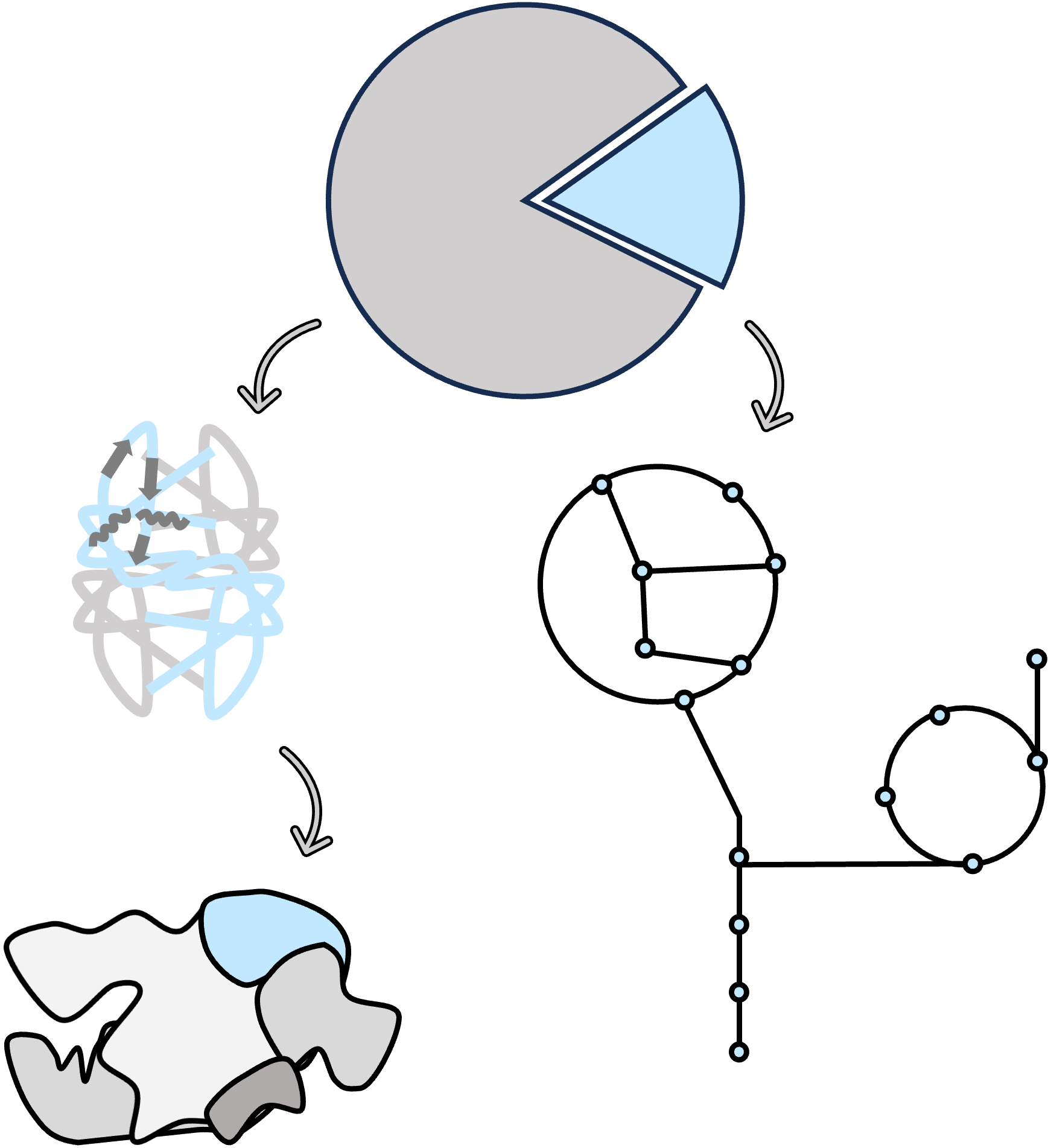

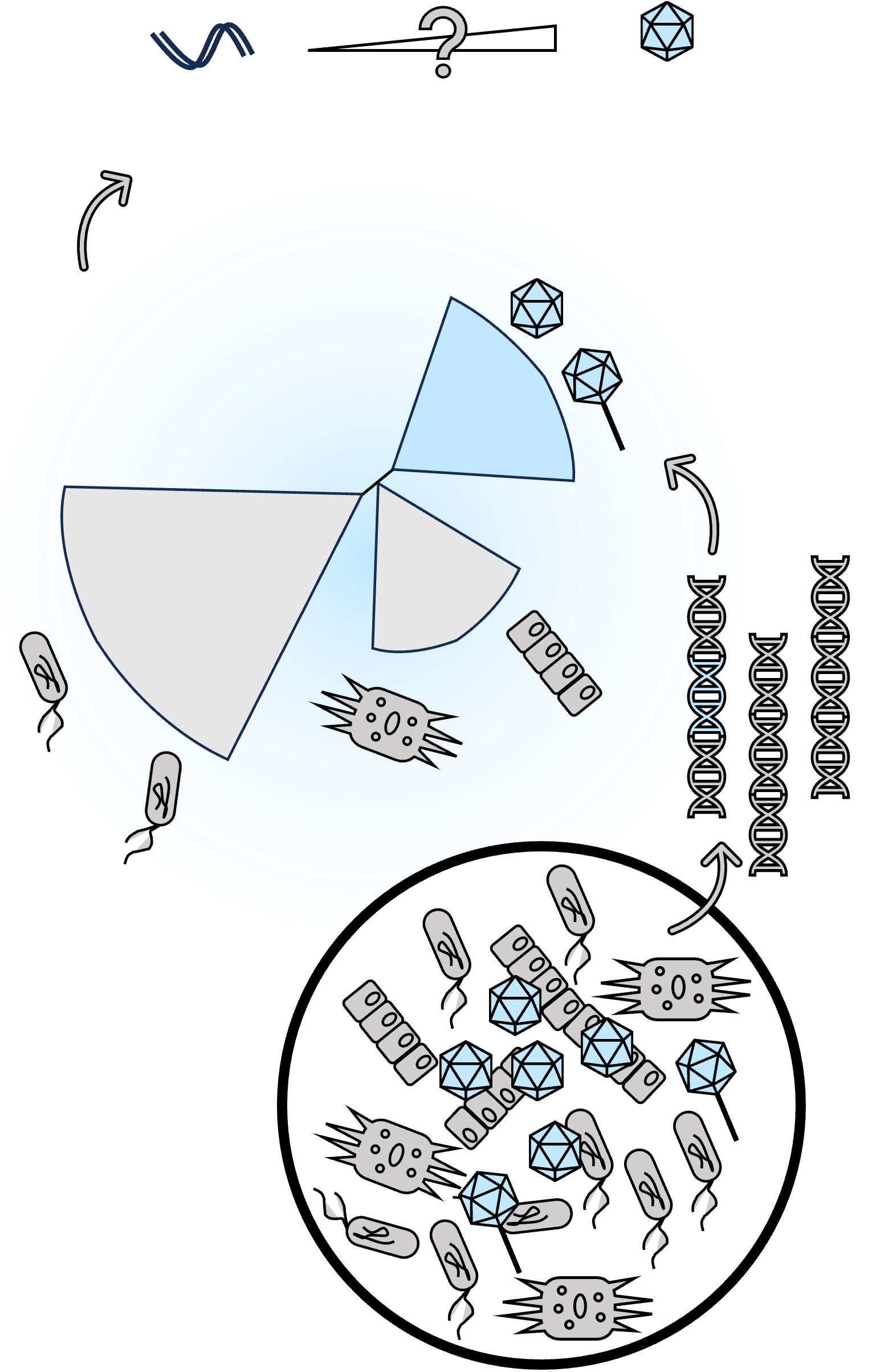

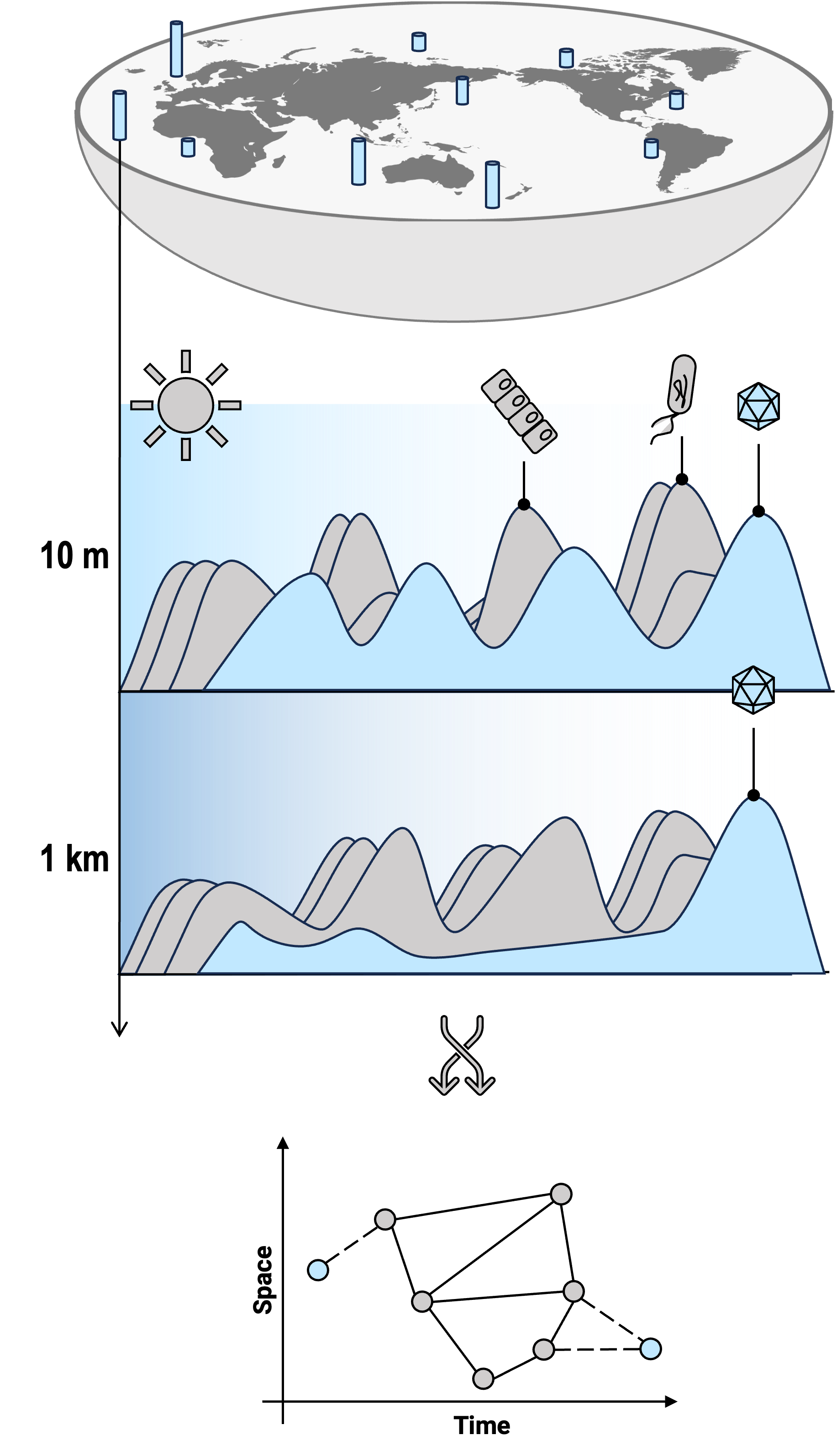

In giant virus studies, traditional approachs are limited to approximately 100 species-level isolates obtained through laboratory co-cultivation with a narrow range of protists and algae. Differently, metagenomics enables the discovery and analysis of these viruses directly from environmental samples, which reveals the broader diversity and global distribution of giant viruses. Extended environmental viruses possess complex genomes with genes related to host manipulation and metabolism. Overall, metagenomics helps answer key questions about viral evolutionary relationships, functional potential, and ecological roles, such as how they influence microbial communities and biogeochemical cycles.

However, each approach has its limitations. For me, it is painful to discover thousands of giant viruses without knowing what hosts they infect. I can only generate hypotheses without being able to validate them. While I enjoy my work, I am not satisfied at the same time. I give me a small, fundamental but general questions, and for each one, I am deeply eager to find the answers: Who are they (Biodiversity)? Where are they (Biogeography)? When do they appear (Dynamics)? What do they infect (Host range)? How do they infect (Infection cycle)? Why do they become so (Evolution)?

These questions are simple yet complex. While some have been partially answered, this is not the end. I aspire to push the boundaries of knowledge further through my efforts. To achieve this, I have structured my work around few directions.

Diversity and evolution

Currently, the ICTV database includes around 10,000 experimentally validated virus species. However, metagenomic analyses have revealed orders of magnitude more viruses, many of which were previously unculturable and remained undetected by traditional methods. Generally, detecting viral diveristy is challenging, because but not limited to the following reasons: 1) Giant viruses are generally less abundant than cellular organisms in environmental samples and have smaller genomes 2) Viruses exhibit high diversity but lack a universal marker gene like cellular organisms; 3) Giant viral genomes often contain many repetitive sequences and high intraspecies diversity, making it difficult to obtain complete genome assemblies 4) There are only few reference genomes with isolated hosts

In bioinformatics, what we can do is improve the pipeline and our logic of finding viruses. An effective approach is to focus on the most universal genes. By doing so, we discovered a phylum-level new lineage related to herpesviruses, named "Mirusviricota" (Nature 2023). Another approach is to define a flexible core gene criterion for giant viruses, which helps identify a large group of EsV-related viral genomes (mSystems 2024) and more than 1000 new species. In addition to free-living virions, screening for viral signals in eukaryotic genomes has also surprisingly revealed a large amount of dsDNA viral regions (Preprint 2025), of which there is a 1.5 Mb one (Virus Evolution 2023).

Why should we study viral diversity and genomic diversity? Because genomic information, some how like fossils, offers us insights and guidance for the evolution. The evolutionary history of giant viruses remains a subject of ongoing debate and uncertainty. The most accepted hybrid hypothesis suggests that giant viruses evolved from smaller eukaryotic dsDNA viruses. The mosaic feature of mirusviruses suggests that herpesviruses evolved from tailed bacterial viruses via ancestral protist-infecting viruses via ancient horizontal gene transfer (HGT) events (Nature 2023). Similarly, HGTs among viruses represents a important evolutionary mechanism that shapes Nucleocytoviricota virus gene repertoires (Molecular Biology and Evolution 2024). One possible driving force, out of the host interaction, is the co-adaptation to harsh environments (Nature Communications 2023).

Giant viruses are widespread, abundant, and active in the ocean. Endemism was observed that a considerable proportion of unique populations have been found specifically in the Arctic Ocean (Nature Communications 2023). Besides the open ocean, giant viruses have also been detected in various aquatic environments, such as a eutrophic coastal inlet (mSystems 2024) and deep freshwater lakes (ISME J 2024). Giant viruses exhibit specific dark water temporal patterns. Overall, aquatic ecosystems harbor far more giant viruses than terrestrial or host-associated environments. However, a pithovirus lineage was discovered in numerous clinical patient samples across a three-year duration, and was also detected in widespread underground water samples (Coming Soon). In addition, other eukaryotic viruses, such as PLVs (Polinton-like viruses), are also abundant in aquatic ecosystems.

How are these viruses so successful in aquatic ecosystems? We observed a coastal giant virus community exhibits synchronous seasonal cycles with eukaryotes and year-round recurrence (mSystems 2024); nonetheless, most individual viral populations tend to be specialists rather than generalists. And we found that viruses with high microdiveristy tend to be generalists. So, by far I can gvie two strategies for marine eukaryotic viruses: first, by largely shifting their gene repertoires to adapt to changing hosts and ambient environments; and second, by accumulating sufficient mutations, which enhances their resilience and adaptability within complex ecosystems. Do I believe they are all the answer? Definately no.

Distribution of eukaryotic viruses

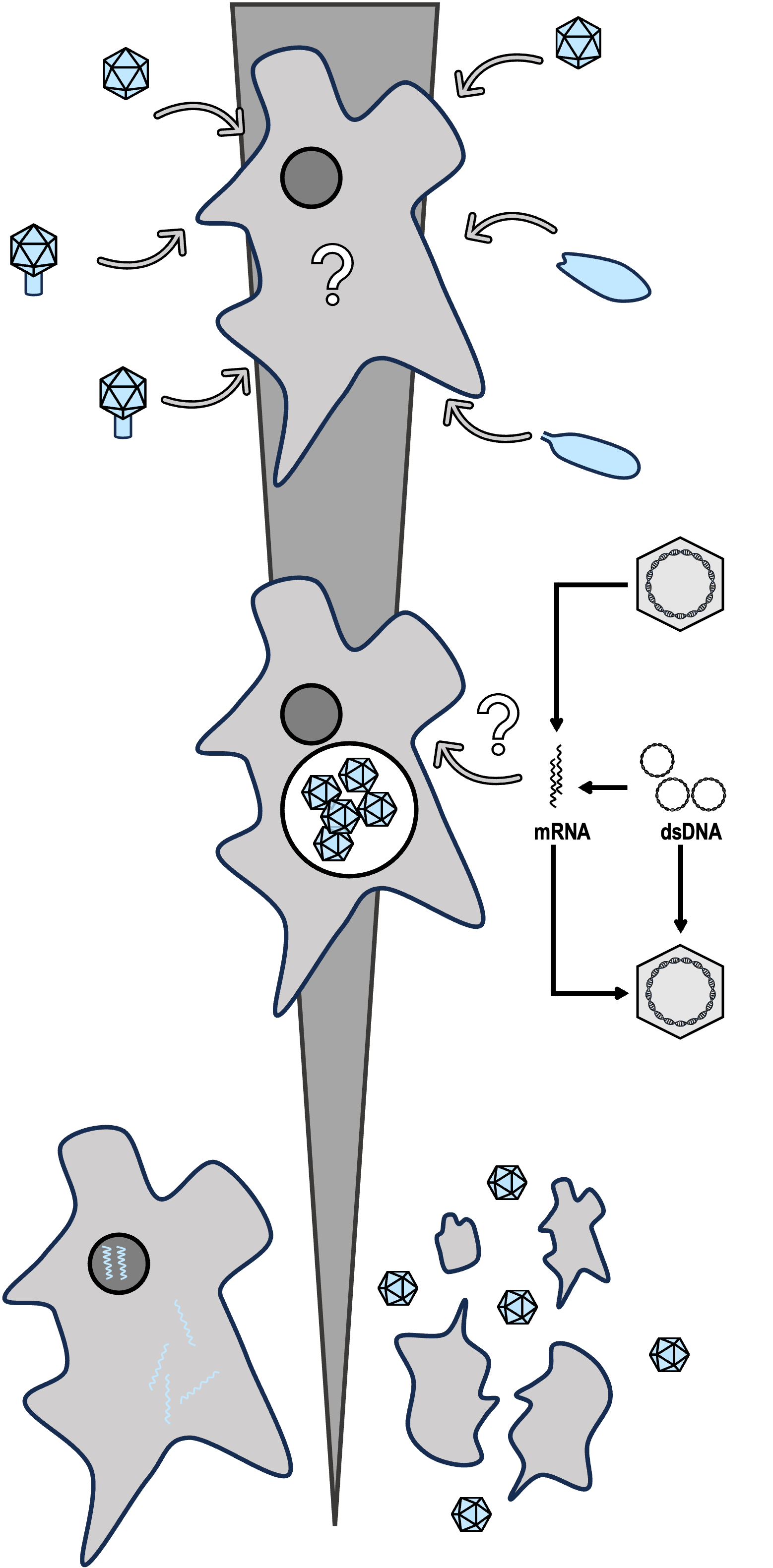

Host infection

We are familiar with classic predator–prey dynamics in macroworld, such as pair between wolves and rabbits. But the microscopic world is equally fascinating. Viruses, unlike other cellular predators, can only replicate by infecting a host cell, making them entirely dependent on their hosts for survival and showing diversed living strategy with their hosts. One common viral strategy is to kill the host through lysis, a phenomenon often described by the "killing-the-winner". This also applies to some giant viruses; for example, HaV has been shown to terminate blooms of Heterosigma akashiwo and could be demonstrated using metagenomics (Coming soon). However, not all eukaryotic viruses follow this lytic path. Many eukayotic viruses establish persistent infections or integrate into host genomes. More profoundly, viruses may have played a crucial role in driving the evolution of eukaryotes (Communications Biology 2025).

To uncover these intricate virus–host relationships, model virus-host systems are essential and this cannot be fully resolved through metagenomics alone. I am committed to contributing to this challenge by learning more and more techniques. Although limited in experimental validation, bioinformatics provides valuable opportunities for predicting virus–host relationships. My first research on giant viruses focused on developing methods to evaluate and improve the accuracy of host predictions using co-occurrence networks and phylogenetic analysis (mSphere 2021). In addition, approaches such as detecting HGT events (Nature 2023) and screening for endogenous viral elements also provide important clues for inferring virus–host associations (Curr Biol 2024) .

Understanding viral functions is essential for revealing how viruses interact with their hosts, influence ecosystems and have evolved. Most of people believe that all viruses need to do is replicate themselves. So why do giant viruses being gigantism in their genome sizes and functions, such as Pandoraviruses, encode more than 2,000 genes? This seems counterintuitive given their reliance on host machinery. The presence of such large and complex genomes suggests there must be important trade-offs at related to host manipulation, autonomous functionality, or adaptation to diverse environments. Understanding these trade-offs is key to uncovering the evolutionary strategies and ecological roles of giant viruses.